Interview with Silvio Deiaco. Crafting a world where music becomes image, glitches turn into language and identity survives through the need to turn expression into form.

Silvio Deiaco (1999) is a multidisciplinary creative from Predore, a small town on Lake Iseo in northern Italy. His practice moves between design, music, and photography, blending analog experimentation with a strong focus on identity.

The Grammar of Recognition.

For Silvio, the idea of identity is not just a stylistic fingerprint but a compass that guides every project. From his earliest works, the question has never been how to produce images but why they should exist at all.

“When you told me you can recognize my work immediately, that’s probably the best compliment I can get,” he says. Recognition for him is not about self-branding, it is about coherence: a visible line connecting instinct, emotion, and execution. At one point during our conversation, he put it more bluntly: “Without a safe way of expression, I wouldn’t know what to do. Words aren’t enough for me.”

This urgency is what allows him to navigate collaborations without dissolving into them. Some commissions leave space for experimentation, others are more rigid, but the drive remains the same: to leave a mark that is undeniably his.

“I’ve had clients contact me for my style, then suddenly ask for things I don’t even do, like illustrations. At first I would say yes just to help, but I’ve realized it’s better to stay within what feels authentic.” Even in photography—something he still resists defining as his profession—the designer’s eye dominates. At Lost Festival and Club to Club, the first events he ever photographed, he didn’t simply capture moments; he reshaped them through hours of editing until they carried his tone.

“People often ask me if I’m a photographer. I always reply no. I take photos, but I’m not a photographer. For me, images are not just documentation, they are extensions of how I see.”

Design in Stereo.

The real ignition point of Silvio’s practice came from music. He began experimenting visually by recreating album covers on Instagram, fascinated not only by sound but by the design of physical objects: jewel cases, sleeves, vinyl packaging. He immersed himself in books on record cover design, flipping through them until they became part of his visual DNA. “I didn’t even listen to much music before that,” he admits. “But once I started, it became impossible to separate it from visuals.”

This connection matured quickly. What began as playful exercises evolved into real commissions, and eventually into a thesis project that crystallized his philosophy: a book and ten custom vinyl records pressed with music from his collective Universo 48, each adorned with hand-built artwork. For one cover, he sculpted a clay bust from scratch, then photographed it and turned it into packaging. “I woke up one morning and decided I wanted to make a bust. I had never done it before, but I bought clay and spent a week figuring it out. It was rough in real life, but in the photos, with the right light, it became something else entirely.”

Aphex Twin remains a key touchstone. Discovering Richard D. James, and especially Chris Cunningham’s grotesque video for Windowlicker, shifted Silvio’s entire frame of reference. From there he traced backward, digging into old releases, learning how sound and image could operate together as a complete world. “Hearing those records from 20 years ago, you realize they could come out tomorrow and still sound futuristic,” he says. It is no coincidence that his projects today—whether live visuals, album packaging, or experimental zines—are almost always tethered to music. He doesn’t see it as inspiration; he sees it as structure.

“If I had to imagine working without music, I wouldn’t know where to start. It’s the framework that holds my practice together and the spark that turns ideas into something visible.”

Glitch and Memory.

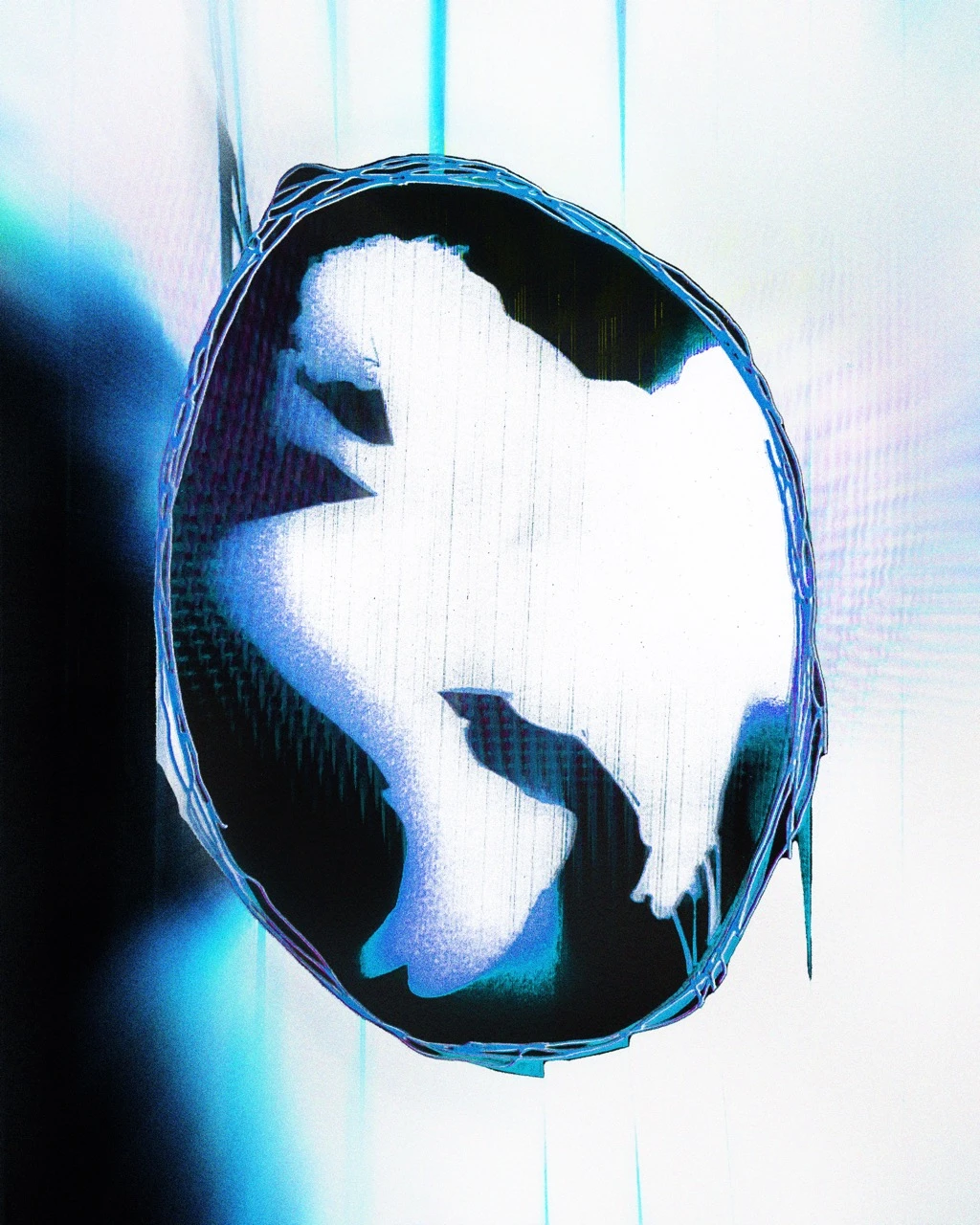

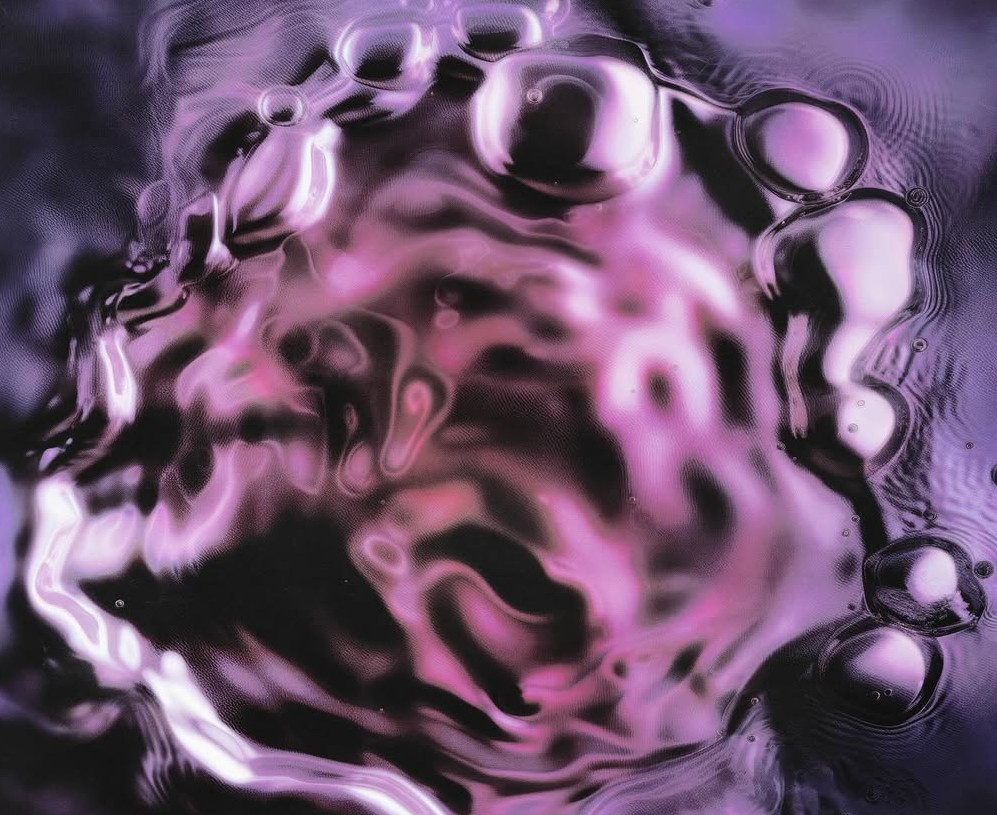

If music is the spark, materiality is the filter through which Silvio processes it. His work is filled with tactile experiments: shooting concerts on VHS, projecting the footage onto CRT monitors, then re-filming the screen to generate analog noise; cutting and scanning paper collages; obsessing over the weight and fold of packaging. “If something can be done both digitally and physically, I prefer to do it physically,” he explains. “Digital alone can look too fake. Analog mistakes have more soul.”

This devotion is not nostalgic, it's practical. Analog methods create a friction that forces him to slow down, to treat images as living objects rather than disposable files.

And yet, Silvio is not dogmatic. He is curious about new tools, particularly AI. He has experimented with Stable Diffusion by reprocessing his own illustrations into altered zines, and he integrated AI-generated textures into music videos like Tripolare’s one.

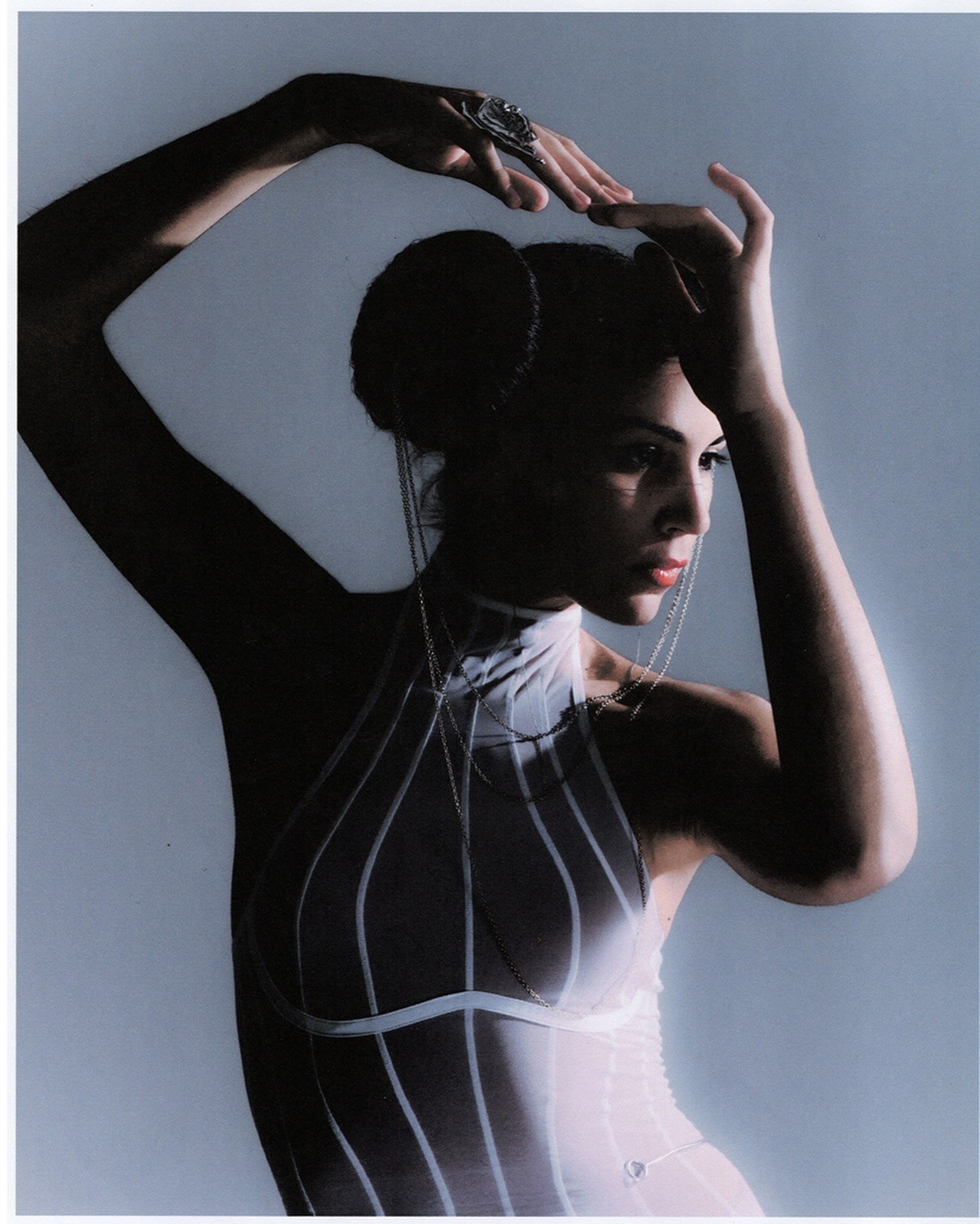

More recently, he collaborated with Marina Herlop alongside Christian Kondić and Dalila (Danilo Gambara; Ed. Note) a project that came together almost by accident. Marina reached out on Instagram saying she’d be performing in Modena and wanted to create something together. Within a week, they had assembled the team and brought the idea to life in a spontaneous, playful way, guided only by curiosity and the joy of making.

But Silvio resists the hype. “I don’t believe much in trends. They move too fast. I see AI as a tool—it depends how you use it. For me, it’s about amplifying something I’ve already done, not replacing it.”

This tension—between analog weight and digital possibility, between DIY instinct and collaborative networks—defines his current practice. It is what makes his work feel both personal and porous: deeply rooted in his own identity, yet open to whatever technology or collaboration might come next. “I started because I liked doing it, not to follow a trend,” he says. “If you want something to grow, you have to enjoy it first.”